Introduction

If you want to implement interprocess communication, you will end up reading about pipes and file descriptors. The problem I found is that .NET does a great job hiding all these concepts from us. I don’t know about you, but I didn’t even know much about these concepts until I needed to implement some interprocess communication.

Motivation

Most headless browsers, e.g. Chromium, have the ability to communicate with a parent process, whether using WebSockets or Pipes.

The problem is that I was never able to implement pipes on Puppeteer-Sharp, and I really want to implement it on Playwright-Sharp.

So let’s see how far are we from getting this done.

Communicating two Node.JS processes

Implementing pipes in Node.JS it’s pretty simple and straight forward.

Let’s say I have a parent and a child app. When the parent app creates the child app process, it will be able to set up the child’s stdin (File descriptor 0), stdout (File descriptor 1) and stderr (File descriptor 0), but not only that, it will also be able to create more file descriptors, which can be used as an extra set of pipes.

const server = childProcess.spawn(

'node',

['../child/index.js'],

{

stdio : ['inherit', 'inherit', 'inherit', 'pipe', 'pipe']

}

);

In this call, we are not only setting up stdin, stdout, and stderr, but we are also creating two pipes using the file descriptor 3 and file descriptor 4.

Let’s create two small scripts to test this. We will write a parent app which will read an input from the terminal, it will send it to the child app, and the child app will echo it.

The parent app would look something like this:

const readline = require('readline');

const childProcess = require('child_process');

// Create child process

const server = childProcess.spawn(

'node',

['../child/index.js'],

{

stdio : ['inherit', 'inherit', 'inherit', 'pipe', 'pipe']

}

);

// We will use the File descriptor 3 as a writer and the File descriptor 4 as a reader.

const reader = server.stdio[4];

const writer = server.stdio[3];

const rl = readline.createInterface({

input: process.stdin,

output: process.stdout

});

// When we get data on the reader we print it

reader.on('data', data => console.log(data.toString()));

// We are going to send a message to the child

var waitForMessage = function () {

rl.question('', (message) => {

if(message === 'exit') {

rl.close();

}

writer.write(message + '\n');

waitForMessage();

});

};

waitForMessage();

The child app will be super simple:

const readline = require('readline');

const fs = require('fs');

// We will create an stream reader from the file descriptor 3

const reader = fs.createReadStream(null, {fd: 3});

// And a writer from the file descriptor 4

const writer = fs.createWriteStream(null, {fd: 4});

// When we get a message on the reader we echo it in the writer

reader.on('data', data => writer.write('echo: ' + data + '\n'));

// This is how a .NET developer leaves an app open in Node.JS

setInterval(()=> {}, 1000 * 60 * 60);

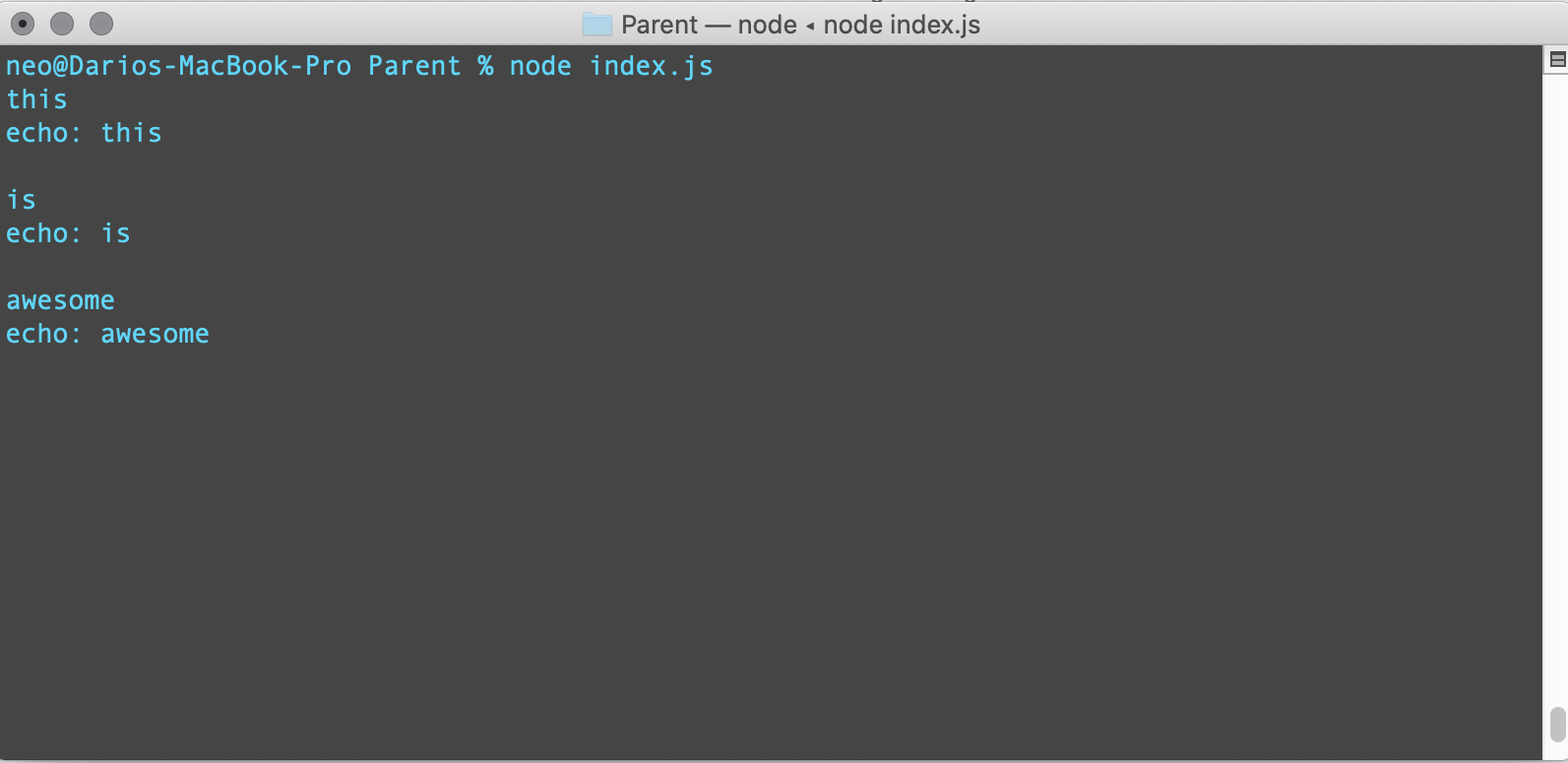

So far, so good. It works

Now, let’s get to the important part. Can I connect a .NET app there?

.

.

.

.

No, you can’t. It’s not possible to add more streams on a Process instance in C#. You will find a way better explanation here.

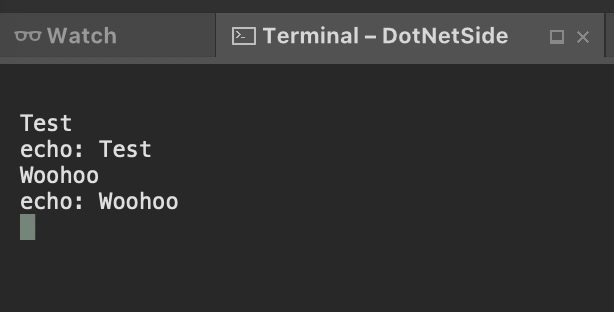

So, our next and final test would be trying to create a .NET app, create new pipes in there, and then passing those file descriptors as an argument to the child app.

The child app would be quite simple. We replace the hardkoded descriptors 3 and 4 with command line arguments:

const readline = require('readline');

const fs = require('fs');

const reader = fs.createReadStream(null, {fd: process.argv[2]});

const writer = fs.createWriteStream(null, {fd: process.argv[3]});

reader.on('data', data => writer.write('echo: ' + data + '\n'));

setInterval(()=> {}, 1000 * 60 * 60);

Now, let’s go to the .NET world. We know there is something called Anonimous Pipes. Let’s see if that works:

static async Task Main(string[] args)

{

// We are going to create two pipes, one writer and one reader.

using var pipeWriter = new AnonymousPipeServerStream(PipeDirection.Out, HandleInheritability.Inheritable);

using var pipeReader = new AnonymousPipeServerStream(PipeDirection.In, HandleInheritability.Inheritable);

// We create a child process passing the pipes handles as string.

Process client = new Process();

client.StartInfo.FileName = "node";

client.StartInfo.Arguments = "../../../../Childwitharguments/index.js " + pipeWriter.GetClientHandleAsString() + " " + pipeReader.GetClientHandleAsString();

client.StartInfo.UseShellExecute = false;

client.Start();

// If microsoft docs tells me to call this method I will.

pipeWriter.DisposeLocalCopyOfClientHandle();

pipeReader.DisposeLocalCopyOfClientHandle();

// We start listening to messages

_ = StartReadingAsync(pipeReader);

// We create a stream writer, and we will write messages on that stream.

using var sw = new StreamWriter(pipeWriter)

{

AutoFlush = true

};

string message = Console.ReadLine();

while (message != "exit")

{

await sw.WriteAsync(message);

message = Console.ReadLine();

}

client.Close();

}

private static async Task StartReadingAsync(AnonymousPipeServerStream pipeReader)

{

try

{

StreamReader sr = new StreamReader(pipeReader);

// This method should get a CancellationToken so we use that instead of a while true.

// But this will work now.

while (true)

{

var message = await sr.ReadLineAsync();

if (message != null)

{

Console.WriteLine(message);

}

}

}

catch (Exception ex)

{

Console.WriteLine(ex);

}

}

Final Words

It was so cool to find that we can implement this kind of solution between both frameworks. I know that implementing pipes is not something most of us need in our daily job, but you know, maybe someday you will need to connect to a browser using these pipes 😉.

If you want to take a look at the source code, you can find the repository on Github.

Don’t stop coding!